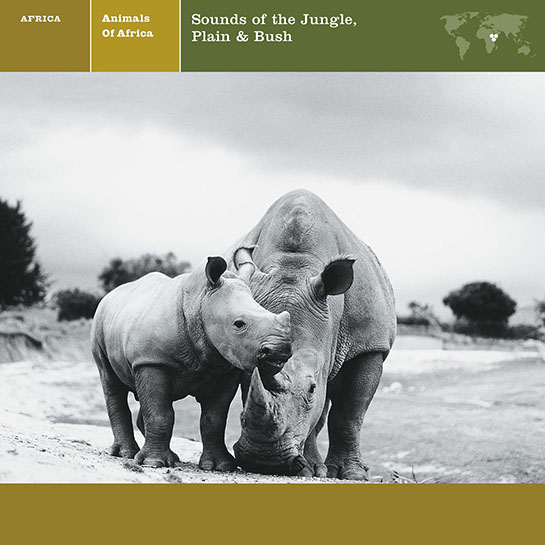

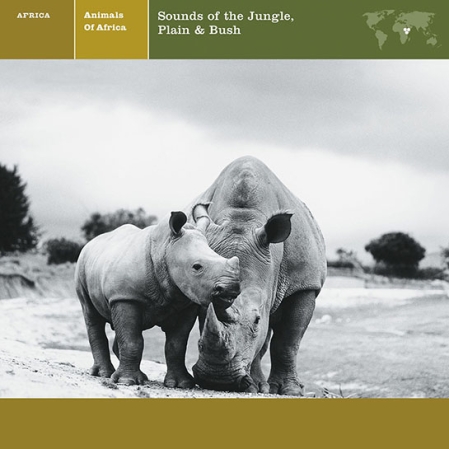

Wildlife as they are, recorded in Kenya and Tanzania in 1973. The leopard, vervet monkey, hippopotamus, hyrax, zebra, wildebeest, lion, hyena, wild dog, silver-backed jackal, elephant, and the unforgettable “love-call” of the rhinoceros.

Originally released in 1973

In order to provide a historical context for this recording, the liner notes that accompanied its original release have been reprinted in full below. The text has not been edited to reflect changes in general cultural perceptions or specific factual information that may have occurred since then.

In the years following the release of this record, biologists in Kenya discovered that vervet monkeys possess a genuine vocabulary that they use to differentiate the various predators around them. One particular noise was determined to be the actual word for “eagle,” which, when vocalized, incites nearby vervets to direct their attention to the sky; intoning a certain bark, understood to mean “leopard,” sends them scurrying for shelter amid the treetops. Further studies deciphering sounds within this lexicon have eroded the previously held notion that humans are the sole possessors of word-based communication.

—Ed.

Current research among naturalists tends to break down any remaining class-distinction between animals and man; the more we know about the other creatures on our common planet, the sillier it seems to judge homo sapiens either as superior to all others, as the ancients dreamed, or as the lowest conceivable form of beast, as some of us might suspect today. It turns out that nearly everything we thought unique to our species – city-building, war-making, tool-using, the ability to employ logic – can be already found in some other animal’s daily behavior. Even a cursory listening to this record will dispel the notion that we are the sole possessors of the concept of language: I am sure that at least some of these animals’ speech is as articulate as ours – all we lack is an effective interpreter, a Rosetta stone that would let us in on their secrets. But for me, as a composer and musician, the most fascinating aspect of these animal sounds is their musicality, their phrasing. There is never any un-clarity or tentativeness in their statement, and that is enviable from any artist’s standpoint. Children have this directness, but when we grow up we becloud our speech, befog our meaning, lose our animal voice. Half the struggle of any good singer, actor, instrumentalist, or composer is to find that voice again, to recreate with great care what seemingly comes naturally to the hippo or the leopard. Some of us almost succeed in this, and that is why we respond so strongly to a Billie Holiday, to a Mozart, to a Varèse. It should be unnecessary to say what follows, but I think I must. Listening to this recording in the relative safety and confinement of one’s living room could lead all too easily to the waggish parlor-game of finding amusing parallels between, say, the cry of the hyena and the opening of Varèse’s Intégrales, the trumpeting of the elephant and a fanfare in a Mahler symphony, the chattering of the vervet monkey and that of the strings in a Beethoven scherzo. There exist, already, recordings in which bird and animal “noises” have been electronically reprocessed to make little tunes; I need hardly mention the craze, a few years ago, for jungle sounds accompanied by filtered-in sentimental music. All this shows a lack of respect for the animals themselves, for the dangerous and blazing beauty they possess and we have so often lost in our circumscribed lives. The African recording engineers have done well to give us the voices of their wildlife as they are, where they are, in the forest, bush, hillside, and savannah of an enormous continent few of us have visited, and we are privileged for the gift. Listen carefully, and even some of the language-barrier between man and beast disappears; I find, for example, the passionate love-call of the “unbeautiful” rhinoceros as moving as anything in human music. - WILLIAM BOLCOM, 1973

PRODUCTION CREDITS

Originally released in 1973 (H-72056).

Produced by High Fidelity Productions Ltd., Nairobi, Kenya

in cooperation with A.I.T. Records (Kenya) Ltd., Nairobi

Mastered by Robert C. Ludwig at Sterling Sound, Inc.

Coordinator: Teresa Sterne

Re-mastered by Robert C. Ludwig

Design: Doyle Partners

Photograph: © Michael Nichols / Magnum Photos

Southern White Rhino and Calf.

The East African Wildlife Society, P.O. Box 20110, Nairobi, Kenya (www.eawildlife.org), performs magnificent preservation work in behalf of the animals of Africa; we hope this album will draw increased support for their efforts.

79705