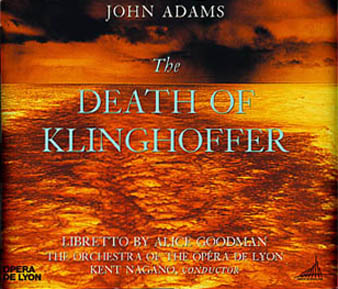

Composer John Adams's 1991 opera The Death of Klinghoffer received its Metropolitan Opera premiere last night, the first of eight Met performances during the 2014–15 season. The opera, with a libretto by Alice Goodman, was originally directed by frequent Adams collaborator Peter Sellars. It addresses the 1985 hijacking of the Achille Lauro ocean liner and the murder of a Jewish-American passenger, Leon Klinghoffer, by Palestinian terrorists. Nonesuch Records released the first recording of The Death of Klinghoffer, with the Orchestra of the Opéra de Lyon, in 1992. Here, Nonesuch President Robert Hurwitz offers his reflections on the piece and some background about the 1992 recording

Composer John Adams's 1991 opera The Death of Klinghoffer received its Metropolitan Opera premiere last night, the first of eight Met performances during the 2014–15 season. The opera, with a libretto by Alice Goodman, was originally directed by frequent Adams collaborator Peter Sellars. It addresses the 1985 hijacking of the Achille Lauro ocean liner and the murder of a Jewish-American passenger, Leon Klinghoffer, by Palestinian terrorists. Nonesuch Records released the first recording of The Death of Klinghoffer, with the Orchestra of the Opéra de Lyon, in 1992. Here, Nonesuch President Robert Hurwitz offers his reflections on the piece and some background about the 1992 recording:

John Adams first told me about the opera in Boston in 1987 when we were finishing the recording of his first opera, Nixon in China, and I was both puzzled and disturbed, as in, “you must be kidding.” I couldn’t understand what he, Peter Sellars, and Alice Goodman were thinking, writing an opera around what seemed to be an undisputedly heinous crime.

We spoke of it little in the next couple of years while he was composing it. In the spring of 1990, I visited John at his home in Berkeley, and I heard the shocking opening of the opera. He showed me the piano/vocal score and played me a MIDI tape of the Chorus of Exiled Palestinians, and even in this most primitive form, the words left me breathless, shaken. I was not prepared for the fury and directness of this chorus and I left John’s house quite upset.

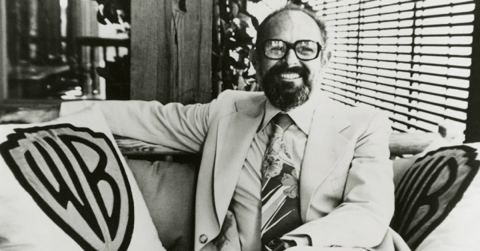

Though I have always tried to make decisions about recordings without being influenced by others, I had to take into consideration the feelings of Bob Krasnow, the chairman of our parent company, Elektra Records, and a brilliant and mercurial man. We were very close, and he knew I was conflicted about Klinghoffer, based on what I had heard. Bob grew up in California during the years of the Holocaust and had strong feelings about Israel. And though unspoken, one of the reasons I was conflicted was that I was concerned about his feelings.

Months before the premiere, Bob and I went to a public discussion of the piece, which included a performance by Stephanie Friedman in the role of Omar, who sings the aria that begins, “It is as if our earthly life is spent miserably…” In essence, it is a fervent declaration by someone whom we would characterize today as a suicide bomber.

When we left the auditorium, Bob was quite upset, and though he fully supported my dedication to John’s music, he called into question whether or not the company could support this recording. It was not a financial question: we already had a proposal from the Lyon Opera that would cover the orchestra and chorus fees, which were by far the largest part of the cost. The issue was whether the company should choose to identify with a work that was clearly, on the surface, troubling.

At that point I was not unlike many of the people who are currently protesting the opera; it was still a mystery to me, I knew nothing of the complete libretto, just two scenes. I had heard only sound bites, a small fragment of the whole.

Over the next few months, John started playing me more music in person, as well as sending cassettes and scores, and as the larger piece began to take shape in my mind, I began to realize that there was far more to it than I had originally imagined. The better I understood the larger picture, the clearer it was that The Death of Klinghoffer was a major and important piece of work, and not only on a musical level. I felt it was crucial for us to record it. To his great credit, Bob Krasnow, despite his misgivings, did not stand in the way.

TWENTY-THREE years later, my sense of the opera has continued to change; the shocks of my first encounters have long since passed, and I have been able to see The Death of Klinghoffer from a less emotional vantage point.

I remember encountering the piece when Penny Wolcott’s filmed version was first shown a year after 9/11, and I once again heard the aria of Omar that I had witnessed when I first saw the piece with Bob Krasnow 10 years earlier. As shocking as the aria seemed when I initially heard it, a year after 9/11 I realized for the first time that John, Peter, and Alice had tapped into something that most of us in America and the West had not considered before the September 11 attacks. We were now on a daily basis hearing language on television and in news reports that seemed right out of Omar’s aria. When it had been in front of us a decade earlier, no one had really heard or understood it.

The creators of The Death of Klinghoffer were not endorsing what was being sung by Omar or Rambo or any of the terrorists, nor the ship captain, nor the witnesses on the boat, nor the Klinghoffers. Rather, they were using this piece to express some of the different perspectives of a problem that was far more troubling than most of us wanted to recognize at the time. They were not asking us to agree with one side or another; they were showing how deeply divided the situation had become. They were asking us to think about what was occurring from as many vantage points as we could, not to treat everything as black or white. In 1991, Omar’s aria was something impossible to grasp; by 2002, it was a part of the language of a complicated world that was all too real.

I have known John for more than 30 years, and I consider him to be a very close friend. I have known Peter for almost as long, and our friendship has deepened in the years we have known one another. In the combined 60 years I have known both men, I never once heard the slightest suggestion of any kind of prejudice about anybody, or any group of people: not a single word, never an intimation. They both have strong opinions about a wide variety of political subjects, they are not of the same mind about many things, and they are, if I could best describe them, two of the most compassionate and sincere people I have ever known.

The creators of The Death of Klinghoffer have been subjected to a great deal of criticism for supposedly taking one side (the terrorists, or the Palestinians) over the other (the Jews, or Israel), but what strikes me about the score is that in John’s music, he treats the two main Jewish protagonists, Leon and Marilyn Klinghoffer, with perhaps as much tenderness as he has ever shown in any of his music. It did not seem to me an act of over-compensation because he might have been concerned about criticism of the piece; it seemed honest and genuinely expressed.

Perhaps what has upset people the most is not that The Death of Klinghoffer took sides, but that it didn’t take sides.

---

I recently saw a show in Washington of the American painter Andrew Wyeth, who in his lifetime was seen in the critical community as a marginal figure, never a subject for a movie (like Jackson Pollock), or a play (like Mark Rothko), never held in much esteem in terms of modern American art. But this show, “Looking Out, Looking In,” was as powerful as any I have ever seen by any post-war American painter, and I was stunned to think that he was seen, both in the critical community as well as by most American museums, as a second-rate figure during his lifetime in the modern art world.

Great artists, and great works of art, mean different things at different times and as time passes, our sense of what those works of art mean also changes. As I look back at The Death of Klinghoffer, now 23 years after its creation, my view of it is still complicated, but I have no doubt it is one of the most important pieces John has written and may be as important as any opera written by anyone in the last 50 years. I recently heard the record again—I am so grateful that we recorded it—and was astonished at the degree the piece does not do what all of its critics say it does—it does not in any way “glorify terrorism;” it is not anti-Semitic. It is a piece of art that takes on one of the most serious political problems the world has faced over the last five decades and given us, Rashomon-like, a dozen different vantage points, none of which it endorses. As writer Mira Sucharov recently wrote in the Israeli newspaper Haaretz:

The desire to distance oneself from understanding lest one accidentally sympathize and hence justify is understandable from a visceral perspective. But to assume that to understand is to justify is a grave intellectual error, one which our society makes at its peril. We can condemn acts of cruelty—as we should—all we want. But to understand, to depict, to draw historical connections, even to give grievances an airing, is not the same as justifying those deeds which may or may not have sprung from them. And most importantly, to solve any problem, one must first comprehend it.

- Log in to post comments