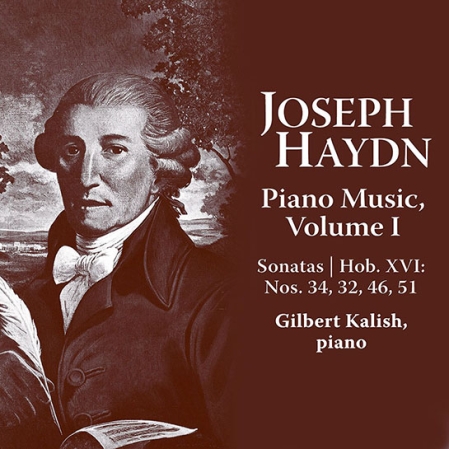

Between 1975 and 1980, Nonesuch released a series of five LPs of pianist Gilbert Kalish performing the rarely recorded Haydn piano sonatas. Now, on the 200th anniversary of the composer's death, the recordings are being reissued, this time as digital albums. Volume I includes the sonatas Hob. XVI: Nos. 34, 32, 46, and 51.

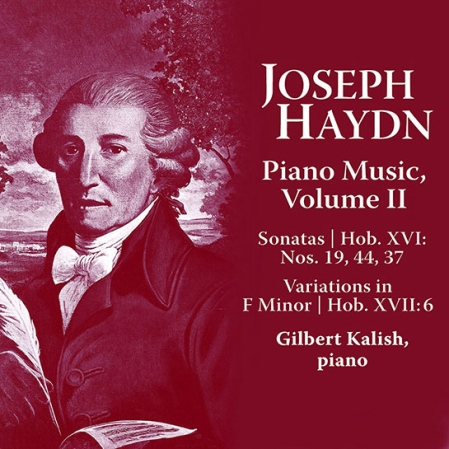

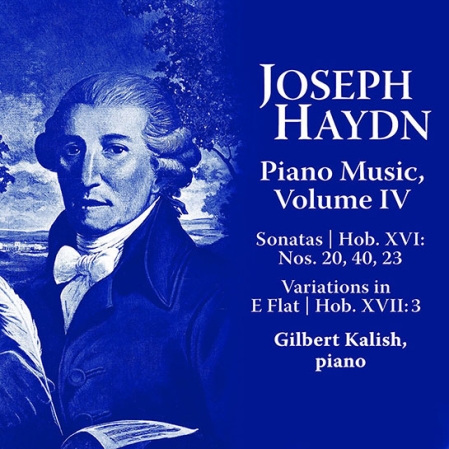

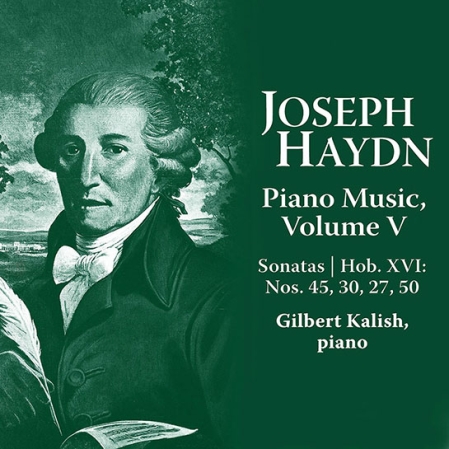

Between 1975 and 1980, Nonesuch Records released a series of five LP recordings of pianist Gilbert Kalish performing piano works—the rarely recorded sonatas and variations—by Joseph Haydn (1732–1809). Now, on the 200th anniversary of the composer's death, the recordings are being issued again for the first time since 1980, this time around as digital albums. Volume I includes the sonatas Hob. XVI: Nos. 34, 32, 46, and 51.

Here, the pianist reveals the story behind and discusses the reaction to the initial recordings:

By 1975, it had become a delightful and well-established tradition for Tracey Sterne, who was then head of Nonesuch Records, to celebrate the conclusion of a recording project by opening a bottle of good cognac and sharing it with the artists and producers in a spirit of relaxed satisfaction. At the time, I had just finished a particularly difficult recording session, at the end of which my collaborator (who shall remain nameless) stormed out without a word to anyone.

Even amidst the turmoil, dear Tracey continued her lovely post-recording tradition, and while we were all at our ease and in a mellow frame of mind, she said the following to me, "Gil, you really deserve a solo recording after what you've been through this week. What would you choose to do if we gave you that opportunity?"

I answered immediately: the Haydn Sonatas. At that time, these were undervalued, mostly unknown works that deserved a hearing (as is the case even today, nearly 35 years later), and there were few if any recordings of any of them. Tracey jumped at the idea, and that conversation led to the recording of a single LP. It was not meant to be a series of recordings, but the reaction to the music was so strong and positive that the project developed a life of its own, and we did five full-length LPs of the Haydn. Only one of these LPs was transferred to CD at the time, and so this digital release, on the 200th anniversary of the composer's death, makes the entire set available once again for the first time in more than three decades.

—Gilbert Kalish, 2009

Below is the liner note from the original album release in 1975:

Keyboard sonatas of the 18th century evoke visions of intimate settings and cultivated musical amateurs at play. Contemporary reports indicate that sonatas were performed more often in the drawing room than in public concerts. But while many of Haydn’s earliest keyboard works remain comfortably within the formal and expressive boundaries suggested by the surrounding in which they were most often heard, the later ones offer profundity and musical quality rarely encountered in contemporary works of the genre. The singular spirit they radiate encompasses a striking diversity of styles, combining gallant innocence and pre-Romantic seriousness, experimental searching and ironic humor, often within the confines of a single work.

Among Haydn’s instrumental compositions, the sonatas appear closer in style to the divertimenti than to the quartets or symphonies. Yet their formal resourcefulness and incessant variety make them a virtual research laboratory for the symphony. Like the symphonies, the sonatas span nearly all of Haydn’s career—though only three date from the last 20 years of his life. Since many were intended for his pupils rather than for publication, and some have been lost, it is hard to say whether the 62 works included in the most recent critical editions represent Haydn’s total output.

While the title pages of the sonatas typically leave the choice of keyboard instrument to the performer, the music itself shows Haydn’s growing awareness of pianistic values, especially after 1770. The late sonatas explore the dynamic and timbral possibilities of the instrument in a manner hardly predictable from the more neutral figuration of the earlier works.

The charming sonata in A-flat, Hob. XVI:46, probably originated in 1767 or 1768, during the early years of Haydn’s employ with the Esterházy family. Although labeled Divertimento per il Cembalo Solo in Haydn’s Entwurk-Katalog, it differs from the keyboard divertimenti of his older Viennese contemporary G.C. Wagenseil, whose plan—two sonata-form movements and a minuet, all in the same key—Haydn followed in earlier sonatas. Between the opening Allegro moderato and the final Presto comes a delicate sonata-form Adagio in the subdominant, D-flat. The first movement exudes the spirit of the internationalized gallant style so popular in the 1750s and 1760s, although the music definitely bears the mark of Haydn’s own personality. As in many of his symphonies, the development section succumbs to the urgent forward drive of motoric rhythms and harmonically significant pedalpoints, climaxing at a dramatic half-cadence two-thirds of the way through. The more lyric portion that follows, with its impulsive phrase extensions and rhetorical pauses, approaches the manner of C.P.E. Bach’s fantasies. The second movement has been praised as the subtlest piano music Haydn composed in his earlier period. Within a gallant framework of sonata form and perfectly balanced phrase structure, a delicate counterpoint unfolds in first two, then three and four parts, laced with subtly chromatic harmony. The bright concluding Presto typifies Haydn’s predilection for altered recapitulations.

The sonatas in B minor and E minor, Hob. XVI:32 and34, date from the so-called “storm and stress” era of Haydn’s creative life, epitomized by the C-minor sonata Hob. XVI:20 and symphonies Nos. 44, 45, and 49. Characteristics are minor keys, obsessive thematic development, and dynamic rhythmic drive. In this period, Haydn enhanced the dramatic quality of minor-key movements by recapitulating material originally presented in the relative major in the tonic minor—a favorite device of Mozart’s as well.

Composed in 1776, the B-minor sonata foreshadows Beethoven in the rebellious energy of its outer movements. The exposition of the opening Allegro moderato has some of the intensive continuity heard later in Haydn’s London symphonies, where modulatory transitions often outweigh tonally stable passages both in length and effect. Nevertheless, Haydn maintains formal clarity with pregnant silences articulating the larger sections of the sonata design. The second movement contrasts a mild-mannered B-major minuet and a turbulent B-minor trio. Asymmetrical phrases and motivic extension create a stylized dance type quite removed from the conventional minuets of Haydn’s earliest sonatas. The intense, agitated Finale is a model of thematic economy. The movement virtually creates itself from its opening repeated-note motive, which undergoes a variety of transformations. Striking canonic and other contrapuntal treatment of the motive throughout the development dissolves into a final powerful unison statement at the close. Fiercely dramatic pauses add to an effect of distraction—quite in contrast to Haydn’s more humorous use of this device in later works.

E-minor sonata, composed in 1781 or 1782, has a similar energy and economy. The opening Presto derives nearly all of its thematic material from its initial motives. Motivic themes easily engender irregular phrasing and unexpected extensions in the recapitulation, where the secondary theme blossoms into a lush sequence and the original closing passages expand into a long and stormy coda. This sort of thematic development became for Haydn a means of both dramatic expression and formal continuity, enhancing the structural breadth already established with slow harmonic rhythm and a simple key scheme, along with his characteristic sense of driving continuity, it was one of the two essential features of Haydn’s style that prepared a way for Beethoven.

The sonata-form Adagio in G major untold as if it were a variation of an unnamed song, languorous with chromatic elaboration, then drawn out by rhapsodic extension of the basic song-like periodicity. The movement ends surprisingly: a deceptive cadence and modulation to E minor suddenly darkens the mood, creating a transition to the finale that ceases ominously on the dominant chord—one of the few instances within Haydn’s sonatas in which movements are connected.

The final Vivace molto has a curious form best describe as a double theme and variations. An innocent binary song in E minor alternated with a similar melody in E major. Each is varied in turn, resulting in an overall ABA1B1A2 design. Dual variations of this sort, found earlier in keyboard pieces by C.P.E Bach and G.B. Martini, were a favorite device with Haydn, who used this procedure in other sonatas, notably Hob. XVI:33, 40, and 48, and in several quartets and symphonies as well.

The D-major sonata Hob. XVI:51 was probably composed in 1794 or 1795 as one of three intended for Therese Jansen, an accomplished English pianist and pupil of Clementi whose marriage to engraver Gaetano Bartolozzi Haydn witnessed in 1795. It is the last of his eleven two-movement sonatas. The opening Andante unconventionally uses sonata-rondo form, usually heard only in final movements. The closing Presto is in rounded binary form, but with the repetition of the second portion written out without any changes—as if to ensure its inclusion.

If the emotional, empfindsame quality of the early 1770s resurfaces in the late sonatas, the D-major also shows the playful galanterie of the earlier period ceding to a warm Romantic lyricism. Short-breathed opening statements give way to a cantabile melody in octaves over a rippling triplet accompaniment, which, with the rather loose overall thematic construction, arouses associations with Schubert. On the other hand, textural and rhythmic features of the finale more nearly suggest Beethoven, especially the perverse rhythmic accents, which temporarily displace the metric downbeat to the previous third beat.

In representing a broad ranger of styles, these four sonatas show the diversity, both of substance and treatment, found throughout Haydn’s music. It is fitting that the age that produced Captain Cook, whose explorations widened the horizons of European imagination, should also have produced a composer capable of widening musical horizons by his mastery and synthesis of diverse musical styles while creating compelling works of art.

—Judith L. Schwartz, 1975

PRODUCTION CREDITS

Engineering and Musical Supervision: Marc J. Aubort and Joanna Nickrenz, Elite Recordings Inc.

Original album mastered by Robert C. Ludwig, Sterling Sound Inc.

Coordinator: Teresa Sterne

Album originally released as H-71318 in 1975

519787

MUSICIANS

Gilbert Kalish, piano