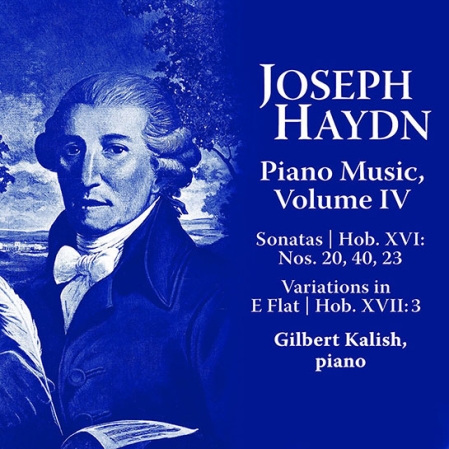

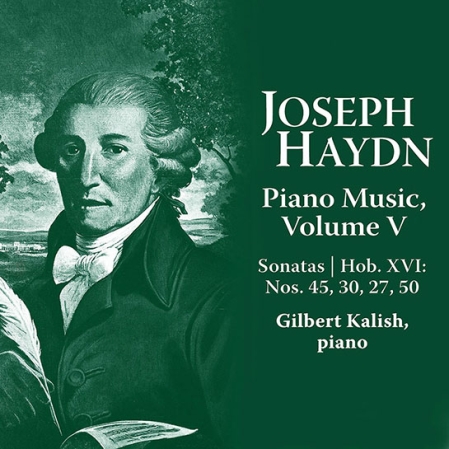

Between 1975 and 1980, Nonesuch released a series of five LPs of pianist Gilbert Kalish performing the rarely recorded Haydn piano sonatas. Now, on the 200th anniversary of the composer's death, the recordings are being reissued, this time as digital albums. Volume IV includes the sonatas Hob. XVI: Nos. 20, 40, and 23, as well as Variations in E flat, Hob. XVII:3.

Between 1975 and 1980, Nonesuch Records released a series of five LP recordings of pianist Gilbert Kalish performing piano works—the rarely recorded sonatas and variations—by Joseph Haydn (1732–1809). Now, on the 200th anniversary of the composer's death, the recordings are being issued again for the first time since 1980, this time around as digital albums. Volume IV includes the sonatas Hob. XVI: Nos. 20, 40, and 23, as well as Variations in E flat, Hob. XVII:3.

Here, the pianist reveals the story behind and discusses the reaction to the initial recordings:

By 1975, it had become a delightful and well-established tradition for Tracey Sterne, who was then head of Nonesuch Records, to celebrate the conclusion of a recording project by opening a bottle of good cognac and sharing it with the artists and producers in a spirit of relaxed satisfaction. At the time, I had just finished a particularly difficult recording session, at the end of which my collaborator (who shall remain nameless) stormed out without a word to anyone.

Even amidst the turmoil, dear Tracey continued her lovely post-recording tradition, and while we were all at our ease and in a mellow frame of mind, she said the following to me, "Gil, you really deserve a solo recording after what you've been through this week. What would you choose to do if we gave you that opportunity?"

I answered immediately: the Haydn Sonatas. At that time, these were undervalued, mostly unknown works that deserved a hearing (as is the case even today, nearly 35 years later), and there were few if any recordings of any of them. Tracey jumped at the idea, and that conversation led to the recording of a single LP. It was not meant to be a series of recordings, but the reaction to the music was so strong and positive that the project developed a life of its own, and we did five full-length LPs of the Haydn. Only one of these LPs was transferred to CD at the time, and so this digital release, on the 200th anniversary of the composer's death, makes the entire set available once again for the first time in more than three decades.

—Gilbert Kalish, 2009

Below is the liner note from the original album release in 1979:

In Haydn’s entire piano oeuvre, the Sonata in C minor, Hob. XVI:20, stands as his single but monumental contribution to the Sturm und Drang movement. Although Sturm und Drang (“Storm and Stress”) is a literary term taken from a play by Klinger (1776), the Austrian school of composers, led by Haydn, began its own “Storm and Stress” about 1766–67, antedating the literary movement by several years. The C-minor sonata was composed in 1771; that year and the following one witnessed the climax of Haydn’s cultivation of the Sturm und Drang: the symphonies No. 44 (“Mourning”), No. 45 (“Farewell”), No. 52, and the String Quartets, Op. 20. In 1773 he abandoned this style for the formally clear, musically fresh and uncomplicated writing of the six Piano Sonatas, Hob. XVI:21–26, dedicated to Prince Nicolaus Esterházy. If, with the “Farewell” Symphony (first performed November 1772) the “Storm and Stress” reached its apogee, it is surely significant that a radically different style makes its appearance in the works written almost immediately afterward for Esterházy: the Missa Sancti Nicolai (first performed December 1772) and the six piano sonatas of 1773.

It is possible that Prince Nicolaus had a hand in Haydn’s return to “normal” music-making; perhaps Haydn was persuaded, in any event, that a work such as the Sonata in C minor could hardly have been expected to entertain the standard concert-goer or pianist in London or Paris. Significantly, when the sonata was published in 1780 by Artaria & Comp., together with the Sonatas, Hob. VXI:35-39 (some of the least profound music Haydn ever wrote), it received a poor notice; for it can only be to the C-minor Sonata that the Almanach musical referred when, in its review of the Artaria set in 1781, it stated:

These sonatas present new ideas and bold turns. One only wishes that there had not been included in the set pieces that do not live up to the composer’s celebrated reputation, due to incorrectness [sic] and a harsh style.

(The critic may have meant also to include in this condemnation the Sonata in C-sharp minor, Hob. XVI:36.) All this aside, the power, and ultimately the profound pessimism, of the C-minor Sonata are qualities that place it far beyond almost any other piano music of the era.

The Sonata in F, Hob. XVI:23 (Landon 38), is perhaps the most striking of the six sonatas of 1773. Haydn’s preface to the first edition includes a dedication in Italian that helps explain why the composer found his employment at Esterháza congenial:

Most Serene Highness! Among the rare attributes and notable qualities which adorn Your Serene Highness, one may count a total possession of music, not only the violin and the baryton [a kind of viola da gamba], which you play exquisitely and at the level of any professional: This knowledge, and the kindness with which Your Serene Highness has up to now looked upon my faithful offerings and encouraged my compositions, have made me bold to dedicate this small part of my talents to your sovereign merit ...

Although the 1773 sonatas are not Sturm und Drang works—they might be called music of the purest intellect—the first movement of the Sonata in F rises in the development to great tension (in a remarkably Scarlattian manner, with brilliant cascades of broken chords). And, aside from the rather dreamy slow movement in F minor—in which the siciliano rhythm and swaying left-hand accompaniment look back to the Italian Baroque—the sonata as a whole shows many forward-looking tendencies. The finale already contains that pointed phrasing and witty concision characteristic of late Haydn, especially in the catchy main subject, which is wholly typical of the composer ten years later.

The Sonata in G, Hob. XVI:40 (Landon 54), is one of three (Nos. 40–42) that Haydn dedicated to Princess Maria Hermenegild Esterházy, who was married to Count Nicolaus (Prince Nicolaus’s grandson). Haydn had always been especially fond of Princess Marie—a musician of fastidious taste—and it was she for whom he composed his last six Masses (1796–1802). The first edition of these three sonatas was issued in 1784, at the time when Haydn began to use an entirely new series of musical terms, one of which is “innocentemente,” a word appropriate to the beautiful opening of the Sonata in G. The sonatas for Princess Marie are also particularly crowded with pianistic terms, the newest of which is “calando.” (The dynamic markings in these sonatas show unmistakably that they were intended for piano rather than harpsichord.) In listening to these works, one cannot avoid the impression that Haydn is treading a thin line, much of the time, in writing for connoisseur, pupil, and professional. Princess Marie was a connoisseur, of course, and that may explain the peculiar charm and cultivation of this sophisticated and gentle music that seems truly to be destined for a lady’s hand.

The theme of the final work heard here, the Arietta con 12 Variazioni, Hob. XVII:3, is taken from the String Quartet, Op.9, No. 2 (ca. 1768–69); in its original form it was perhaps the most beautiful minuet of the period. The variations are artful, intelligent, and have always been popular; but Haydn cannot be blamed if, for all their dexterity, the variations never regain the lambent purity of the theme itself. The melody has been thought to sound Mozartian, and indeed there were manuscript copies of the work circulating in Mozart’s Salzburg a few years after the work was announced in the Breitkopf catalogue of 1774 (one such copy is now in the Städtisches Museum, Salzburg, and is signed “Ex rebus Marthiae Essinger 1779”). Even more Mozartian than the theme are the sophisticated harmonic changes in the accompaniment. Of particular note is Haydn’s masterly use of the top note of his instrument (f’’’) in such manner that one never misses the lack of any higher notes nor has the impression that a more extended treble range would be necessary or even desirable.

—H.C. Robbins Landon, 1979

PRODUCTION CREDITS

Recorded May 1978 in New York City

Engineering and Musical Supervision: Marc J. Aubort and Joanna Nickrenz, Elite Recordings Inc.

Original album mastered by Robert C. Ludwig, Masterdisk Corp.

Coordinator: Teresa Sterne

Album originally released as H-71362 in 1979

519790

MUSICIANS

Gilbert Kalish, piano